by Sven Lindström, CEO, Midsummer

The photovoltaic market continues to grow with impressive speed. Large scale silicon solar parks have been all the fashion until now but thin film panels are becoming increasingly popular and will dominate the small scale off-grid market and the booming building integrated PV segment, especially in sunny regions like Africa.

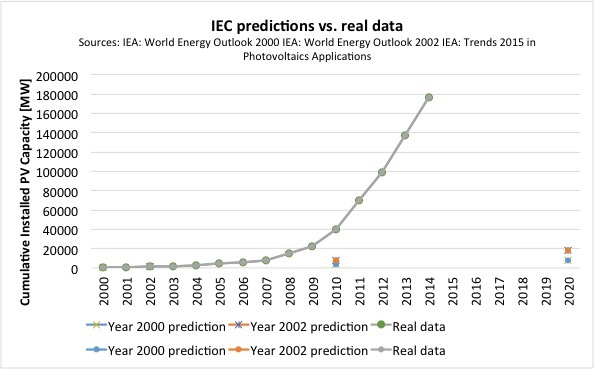

Very few observers were able to foresee the past decades of extremely strong growth in photovoltaic (PV) renewable energy. Even strong supporters like IEA and Greenpeace underestimated the sector’s tremendous growth. Solar energy is now very price competitive with non-renewable energy sources, even without subsidies.

Large scale silicon (Si) producers have contributed to most of the growth in PV. But even if some returned to profitability the margins have remained at disappointing levels. In the thin film segment only two companies, First Solar (CdTe) and Solar Frontier (CIGS) have managed to reach economies of scale and First Solar continues to be the most profitable company in the industry. Actually, very few thin film producers have survived the price pressure and almost all a-Si producers have been wiped off the map.

So, is the conclusion that thin film, just as Si, has to be at large GW scale to be competitive? And why did so few companies manage to scale up their production capacity and process?

First, let us look at what problem all thin film producers has been facing and how they have been handled. I believe that the default of most thin film companies cannot be attributed only to falling prices. Most companies failed on technology rather than market conditions. The problem is that researchers have been chasing world records on smaller and smaller substrate areas. Nowadays world records are made on 0.5 cm2 cells. For researchers this makes sense when trying to understand basic material properties, but for large scale production this type of research has very little relevance.

Supersize model not the way to scale production

If you try to make the best micro-cell in the laboratory and then scale that process up to module size you will face a mountain of problems and costs that will override anyone’s budget and we have seen it happen over and over again. In the a-Si segment the customers of Applied Materials and Oerlikon are all gone. I think the supersize model is not the way to scale production. Mass production does not necessary mean maximum size substrate production.

My research team has taken a different route from the start as they had a background in the optical disc industry, making production equipment for CD and DVD manufacturing. This mature technology was used for the production of CIGS thin film solar cells. As the technology relies on simultaneous parallel processing of several small area substrates, we were able to manufacture 156×156 mm CIGS cells which are interconnected into modules in the same manner as silicon solar cells.

By making cells, instead of large area modules, it has been possible to do all our process development on 156×156 substrates and thereby avoid any upscaling issues. As the substrates are made of 0.15 mm thin ferritic stainless steel, they are flexible and can be used for lightweight flexible modules.

If you have a small substrate you also have small and relatively inexpensive equipment. This also means that you can start from small scale and grow with the market. The ability to reach mass production capabilities from small scale while at the same time keep the ability to scale (by adding multiple identical production lines) is key when developing profitable niche markets.

The three stages of PV implementation

The development of PV implementation looks almost identical in all markets: Stage 1: First you have the off-grid products on a small scale. Products are quite expensive, but still a better alternative than diesel generators or extra battery capacity.

Stage 2: Governments then throw subsidies at grid connected systems in various ways enabling a very fast capacity expansion that mostly end up in large solar parks. This usually results in grid restrains, loud complaints from grid owners and utility companies that see their market positions and profits eroding.

Stage 3: PV on roofs. This is where you utilize the true strengths of PV as the electricity is generated where and when it is consumed. In most populated countries PV is the only natural choice. Instead of burden the grid, the grid is relieved and peak demand is cut.

Today, with the right thin film product, you can be very profitable in segment 1 and 3 above. Segment 2, large PV parks, are best suited for rigid Si-modules and the competition is fierce. However in segment 1, it is possible to sell light weight modules for 6-8 USD/W to the consumer market.

Thin film PV on roof will outgrow the solar parks market

For segment 3, there is an increasing demand for light weight modules that can be installed on any roof without weight constraints. This is where I see a huge market that eventually will be much bigger than the PV parks. Most factory roofs cannot take the load of heavy Si or glass-glass modules without reinforcement. This is where the light weight flexible modules benefits as they are easy to install and even though more expensive than Si, the total Balance of Systems (BoS) cost usually comes out lower than Si.

There is a stage 4: BIPV (Building Integrated PV). All roof-top installations until today are more or less aesthetic add-ons that are placed on top of existing building materials. The future is to integrate PV into roofing materials and facades already at the factory where those building materials are manufactured. EU is enforcing new building requirements that require all buildings to be zero energy buildings from 2020. The only feasible way of doing this is through BIPV.

Building material suppliers not adapting to this change

So are building material suppliers adapting to this change? No, not at all. Companies in Europe and US are very afraid to step outside their core business. So to solve the zero-energy requirements, insulating manufacturers are hoping to add more insulating materials, ventilation companies are hoping to add more ventilation and heat exchange equipment and, companies making heat pumps are hoping to add more heat pumps.”

However, very few companies see the benefit of combining technologies to find new solutions. This is a huge opportunity for visionary companies not only to explore the European and US PV market, but to enable a strong foothold into the multi-billion dollar building material market in EU and US. This stage 4 of PV development is largely undeveloped in all parts of the world.

There has been talk about BIPV for many years, but the market has not really matured. This is because the right products have been missing. There has been a lot of focus on replacing windows with thin film made on glass. This makes no sense. If you put a window in a building you do it because you want to let sunshine in or you want to look outside. If you replace that window with a PV module that is supposed to absorb sunshine you also remove the function of the window. Roofs and facades usually take up a lot more space on a building and make a much better target for BIPV.

If you want a well-integrated product into roofs or facades it has to be light weight, durable and also flexible enough to adapt to the architects vision. CIGS thin film solar cells are ideal for this purpose. A production system like the DUO from Midsummer turns stainless steel substrates into CIGS solar cells. The equipment can be installed in existing buildings and cells are the same size as Si cells and can be assembled in the same way, except that you do not need a glass and aluminum frame. With a Cd-free process you also have no retrains in building integration and the all-vacuum process allows for less stringent clean-room requirements for the production equipment.

In conclusion, silicon solar cells will continue to have a dominant but not so profitable role in the large scale solar park segment. Thin film will find profitable niches in small scale off-grid products and PV on roofs and facades – a huge market that will eventually outgrow large PV parks.

Sven Lindström, CEO, Midsummer

Sven Lindström is co-founder, Chairman and CEO of Midsummer, a leading global supplier of production lines for cost effective manufacturing of flexible thin film CIGS solar cells. Mr. Lindström has over 20 years of experience from international business and development of high tech production equipment and vacuum deposition systems. He has over ten years of experience from the development and management of solar cell production equipment and is a firm supporter of distributed electricity production. See http://www.midsummer.se/.