By Annamarie Bindenagel Šehović

Analysis in Brief: Global health security lies at the intersection of Europe and Africa, between inherited state-based intervention and a new regional, global approach. Given this, it is vital to redefine health security and it is imperative that this new definition include cross-border populations. Likewise, knowledge exchange in both definitional scope and political and experimental approaches across Africa and beyond is an important contributor to health security in a globalised world.

Global health security agenda

Image courtesy: Homeland Preparedness News, 2018

Introduction

Health insecurities know no borders. In Africa, these include not only infectious diseases, but also non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and a context marked by deficits in treatment provision, guaranteed access, and additional support such as clean water and reliable electricity. Especially as pertains to the realities in Africa, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health security is inadequate: first, its prioritisation of ‘national populations’ leaves out non-nationals; second, its reference to the ‘collective health’ of populations across borders fails to clarify this ambiguity; and third, its failure to name who is responsible for health security impedes accountability. Precisely because southern Africa is characterised by both health insecurities and migration, this precludes health security in Africa. This Discussion Paper proposes new parameters for a more comprehensive definition of health security.

A new definition should focus on a key aspect of health security particularly relevant for Africa, namely, the need to address migrant populations beyond the binary of citizens or non-citizens. Whether on the move or sedentary, the health of both is intertwined. This leads to the question: how can it be made possible to address the health security of national populations while also enabling access and adequate treatment to people beyond borders?

Globalisation and population health security

Globalisation and the interconnectedness at its core has never been more apparent. This is true in the arenas of communications, financial transfers and air travel, as well as with regard to climate change, migration and the spread of disease. Health (in)security is a case in point.

Against this backdrop, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health security is increasingly antiquated. According to this definition, health security consists of “the activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimise vulnerability to acute public health events that endanger the collective health of national populations, as well as collective health of populations living across geographical regions and international boundaries”. As befitting an international organisation constituted by sovereign Member States, the WHO depends on the commitment and enforcement of health security measures at the state level. However, this brings with it three limitations:

- The prioritisation of heath security for “national populations”

- The “collective health” of national populations across borders

- By relying on Member States, the WHO leaves unresolved who is responsible for populations that do not or cannot claim a nation.

Consequences of an inadequate definition of health security for Africa

Such definitional problems result in policy gaps. As a consequence of the WHO definition and its state-centric approach, health security is and remains a primarily vertical enterprise. On the national level, this means that health security is implemented via a contract between a national state and its citizens. On the bilateral and multilateral level, the contract is between individual nation states, each of which is responsible to its citizens only.

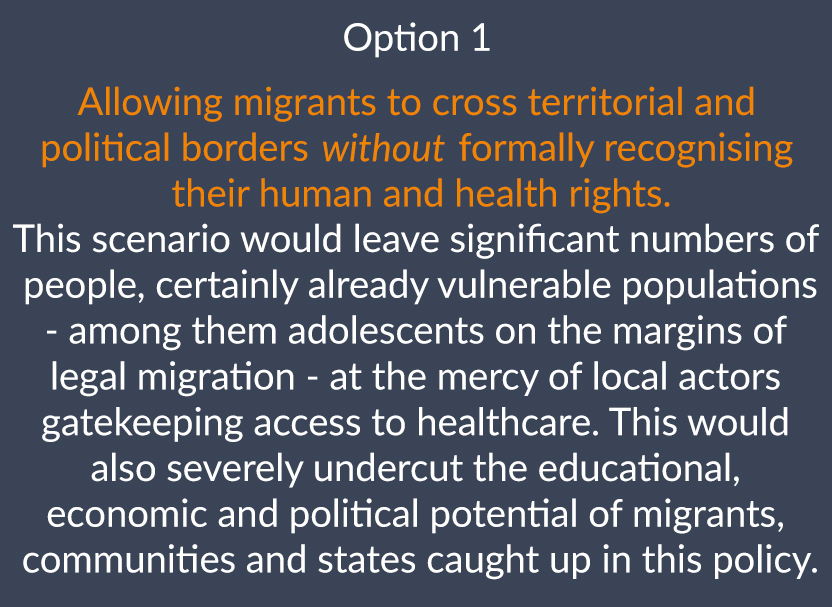

As the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have given way to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there is a shift on the part of the global policy agenda towards addressing broader insecurities more horizontally, involving cross-sectoral partnerships between states and non-state actors as well as businesses and non-governmental organisations. This is exemplified in the shift from the health strategies of the 2000s, which prescribed vertical, or ‘top-down’, disease interventions targeting specific diseases – such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria – to more collaborative and universal approaches. Such a global, horizontal focus that takes into account citizen and non-citizen health security is especially pertinent for Africa, with its high burden of disease, as illustrated in the graph below:

Global disease burden by region

Image courtesy: Our World in Data, 2018

Challenges

Challenges remain. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) these can be categorised on the one hand as internal and on the other as external. Internal challenges include the high burden of disease, both communicable and non-communicable, as well as legal, social and structural determinants such as inadequate access to healthcare, refrigeration, water scarcity, and lack of sewage treatment. These are exacerbated by external challenges such as high levels of migration, including brain drain, and legal weaknesses in the form of unconsolidated states leading to incomplete control of disease surveillance and intervention.

All of these stressors are exacerbated by migration – of disease and of people. Coping with migration is critical for the future of the continent. An overwhelming number of migrants in Africa are adolescents whose health security is at risk. Using different definitions of ‘adolescent’ and ‘young people,’ UNAIDS estimates 1.3 million, whereas UNICEF estimates 1.48 million are living with HIV. Given that many adolescents and young people are also potential migrants, assurance of healthcare for migratory and sedentary populations everywhere in the region is imperative.

Opportunities

Sub-Saharan African states do not have the traditional European luxury of responding to challenges in separate policy spheres (silos), as they almost always have multiple over-lapping crises to address simultaneously. What many sub-Saharan African states do have is experience in cross-border fluidity in terms both of migration and vital, if improvised, access to healthcare. These lessons will become more salient for the region as well as for the world throughout the 21st century.

A new responsive definition of health security could be the first step towards conceptualising and adapting the region’s challenges into an opportunity. My proposal renders health security as a “claim of a safe space for health at the population level; a claim that goes beyond the state-citizen contract.” In doing so, health security corrals the state, as well as sub- and supra-state actors, to conceive and implement – and be held accountable – for regional health security.

Conclusion and recommendations

The WHO definition of health security is dependent upon Member State actions to promote, protect and implement health security. While the definition takes into account “populations living across geographical regions and international boundaries”, its focus is first on national populations. Secondly, it does little to explain which populations are to be included outside of national, state-based definitions of populations.

It is important to note that health security serves as a buttress against identifiable and identified risks and threats. This provides an opportunity for change as two key proponents of health and human security, Germany and South Africa, both accede to the United Nations Security Council as non-permanent members from 2019-2021.

Both countries have significant regional clout to promote and push a new health security agenda at the international scale. South Africa has the added bonus of a decade-plus leadership in niche diplomacy on health. In addition, SADC has launched not only regional protocols on HIV, TB and mental health, but is piloting a project for enabling mobile healthcare access (initially for HIV-positive, long-distance truckers) across the entire region. The southern African experience thus has a chance to serve as a global template.

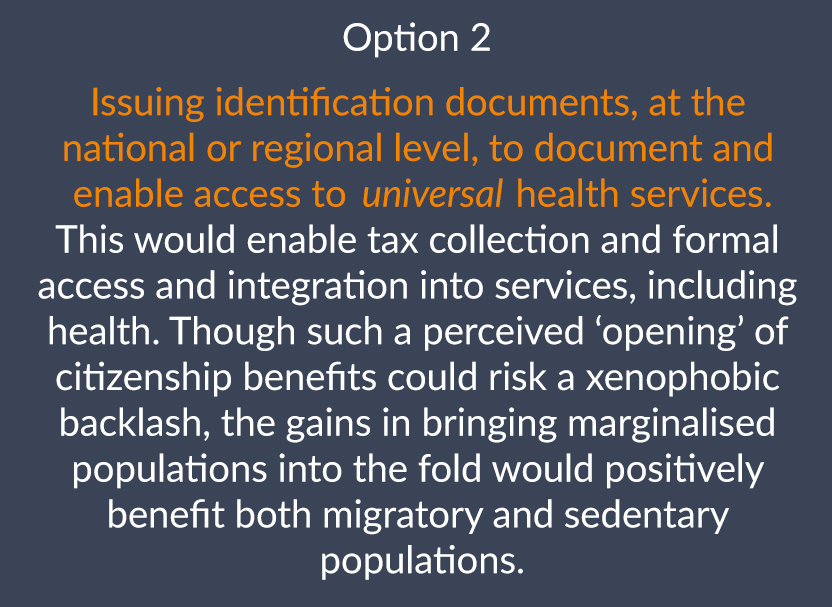

In order to promote a regional definition of health security in practice, two fundamental strategic options directly related to migration present themselves, namely:

TWO STRATEGIC OPTIONS

Based on these strategies, three concrete recommendations reveal themselves:

- First, European partners, especially new leaders in France and Germany, should open a more direct portal to hear and decide whether and how to respond to requests from across Africa, thus drafting a more receptive “Marshall Plan with Africa” that represents genuine partnership.

- Second, to allow open access to scientific and political analysis to identify and promote localized best practice to prevention and treatment, as well as to anticipate and prepare for new and re-emerging outbreaks.

- Third, to share evidence and experience of broadening the definition of health security to include migrants in local and regional health systems, as is being piloted in SADC, at the regional and global levels.

Key Points:

- Health insecurities know no borders. Globalisation and the interconnectedness at its core has never been more apparent. This is true in the arenas of communications, financial transfers and air travel, as well as with regard to climate change, migration and the spread of disease. Health (in)security is a case in point.

- Migration is a key internal and external health security challenge on the continent which health security provisions must address.

- Health security must prioritise interventions to minimise vulnerability to adverse public health events beyond “national populations.”

- Health security must (a) pertain to the health of populations across borders, resolve who or what is responsible for health security for whom, and (c) be addressed at the local, national, international and global levels.

Source: https://www.inonafrica.com/