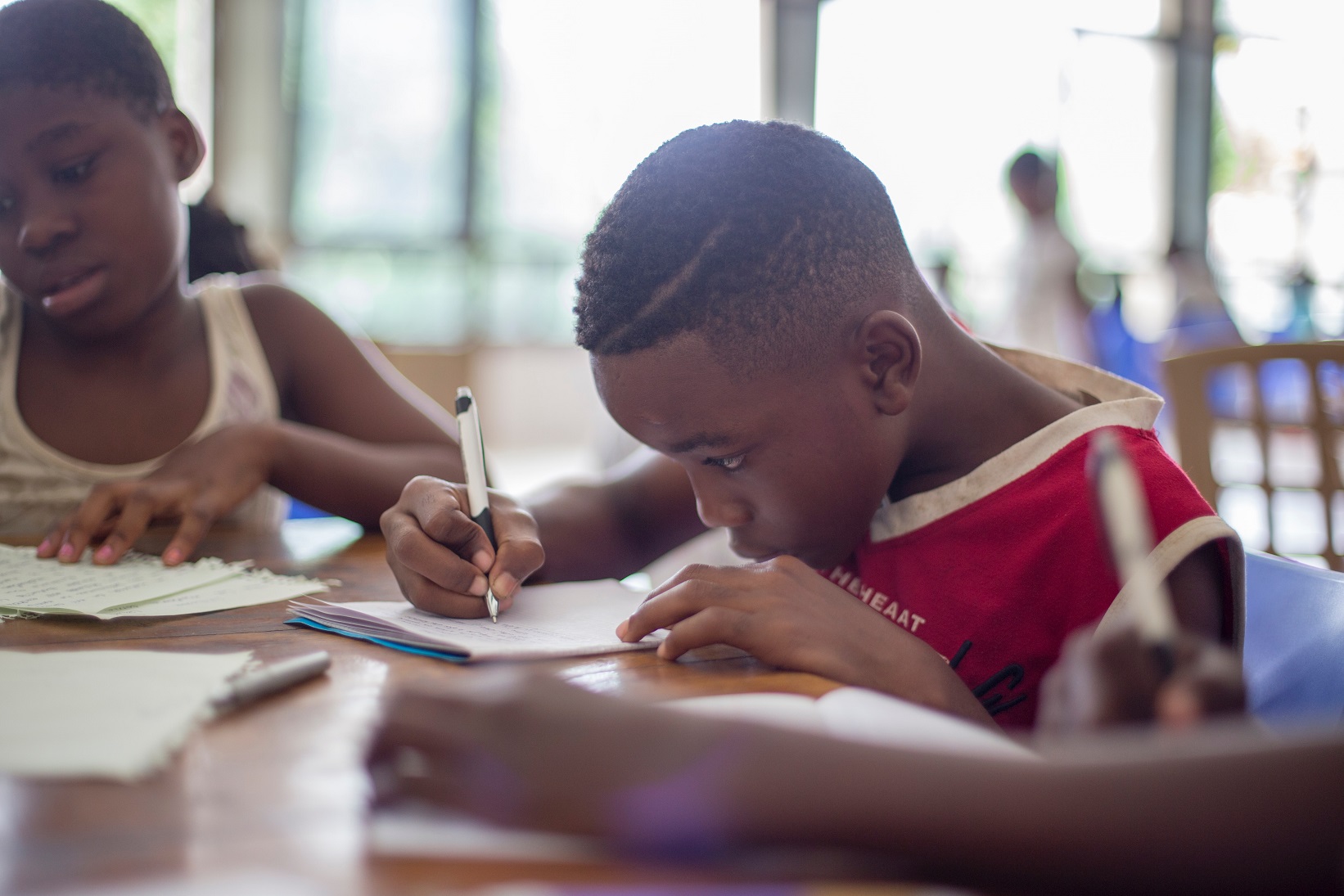

Interviewing N’Gunu Tiny, Founder and Executive Chairman of the Emerald Group about education in Africa.

Finding out about education in Africa, its pre-pandemic trajectory and how it has been interrupted by COVID-19. N’Gunu Tiny talks about how this will further impact social mobility and, crucially, what should be done now?

Discussing education in Africa, the pandemic and more with N’Gunu Tiny

Q: How do you think the pandemic has impacted global education?

There is absolutely no doubt that COVID-19 has negatively impacted global education. However, as with many of the worst effects of the past 15 months of pandemic-based state measures, the hardest hit are those with the poorest and least robust education systems in the first place. And this includes sub-Saharan Africa.

I think that the only way to for Africa’s education system to recover is for governments across the continent to reform education systems totally.

Q: What was the status of education across Africa pre-COVID?

We know from data collected by the likes of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) that Sub Saharan Africa has high rates of exclusion in education. For children between six and 11, there is a 20% rate of education exclusion. When we look at children between 12 and 14, this jumps to 33%. And most damaging of all for the future of Africa, is that 60% of teenagers between 15 and 18 are not in any form of formal education. These figures are from 2019.

Q: Is there a significant gender split within the African education system?

Absolutely. Girls are around 4% less likely to be in education (their exclusion rates are 36% and 32% respectively). In 2018, the UIS did record a slight increase in literacy rates compared with 2017. However, globally at the time, the world’s average literacy rates stood at 86.3%. So, even before the pandemic, there was already an urgent need for educational reform and investment across Africa.

Q: In general, how has COVID-19 impacted education across Sub Saharan Africa

In general terms, the pandemic has highlighted the already present problems with education in Africa. And it is worsening these existing problems. When we talk about a robust education system, we mean those in countries with high numeracy and literacy rates.

These rates are vital to predict the future of the country. The World Bank says that the negative impact of COVID-19 will be felt around the world for generations, with a long-term fall in economic opportunities. And in places like Africa, there was already an enormous challenge surrounding learning and education. It is now indisputably urgent that Governments in countries across Africa start to tackle the gaps in the system.

Q: By gaps, do you mean access to online learning, for example?

Absolutely. One of the stark differences between developing and high-income countries since the pandemic started is access to online education. In developed countries, the immediately obvious way to deal with education was to implement immediate e-learning.

This ensured continuation of education for students at all levels. But in Africa, adopting e-learning has shown clearly the extreme inequality across the region. The digital divide in Africa is very wide. Some countries have relatively high internet penetration in urban areas. However, all countries in the region have poor or non-existent access to the technological connectivity that is essential for online learning to work.

The interesting thing, I think, is that African Governments have been investing in education. According to the African Economic Outlook report in 2020, education investment in Africa stood at 5% of the GDP. This is one of the highest regionally in the world and should mean vast improvements. COVID-19 stopped this in its tracks, and now it’s unlikely that we will see any improvement at all if fundamental policy changes aren’t implemented urgently.

Q: What could the outcome be post COVID-19?

I think it’s absolutely possible that the disaster of COVID-19 could be the catalyst for reform. But this necessitates Governments acting now. They must transform education systems at their core, with a deliberate effort to improve the end result.

Learning must be improved to make it relevant for children today. Education reformers across Africa must now totally reform education systems from primary school through to university. The important thing is that Africa takes its place as a global leader through preparing its younger generations to become the drivers of economic improvement.

It’s time for Africa to change its fundamental systems within education to reflect the regions future aspirations. We can see this to an extent in Ghana, a country that has already made moves towards education reform.

Q: What kind of education reforms are you talking about?

A fully inclusive policy that will really change things for education in Africa means including all children, rural, urban, special needs, poor and well off alike, to have access to the opportunity to succeed. So, inclusive education must be one of the strategies that African Governments embrace and implement.

Basic education should be available to all African children, regardless of where they live, their family background, their socio-economic status or any disability they may have.

Teachers also need much more support in Africa – this is fundamental to closing the education gap. They need to have all of the information and support from educational authorities and for frameworks to be implemented in schools and colleges.

At the first opportunity, African countries should co-ordinate full educational assessments within each country. The data from this can then be used to make the decisions that will work best, all the way from teaching decisions right up to the ministry of education at Government level.

Q: What are the other problems within African education that need tackling?

From studies that I have read, it appears that there is a problem with the appropriate and efficient use of time within educational establishments. Research shows that the problems within general infrastructure and access to teachers and materials results in a gap between intended and actual teaching hours.

For example, information collated by the Human Capital Index in 2018 shows that a child in Sierra Lone spends 2.7 years less in formal education than a child in Ghana, assuming they both start at four years old. While this looks like children in Ghana are better off, actually almost six years of their education is totally wasted. This implies that from 11.6 years at school, children receive education for only 5.7 years.

This just cannot be considered acceptable and remember that this was a few years before the pandemic. As Africa reopens and children being to go back to formal education, Governments across the region must now ensure that this inefficiency is stamped out.

I think also teachers must be supported far more by Governments through formal professional development. Another barrier to e-learning during the pandemic has been the lack of technical experience of the teachers involved.

I hope that African Governments take the experience of COVID-19 and use it as a springboard to completely review the education infrastructure. There are so many inequalities within the system compared with other countries and it’s never been more important to close this education gap and tap into the massive potential of Africa’s young people.